“I want to report how I found the world.” / “Voglio riferire come io ho scoperto

il mondo.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Notebooks 1914–16

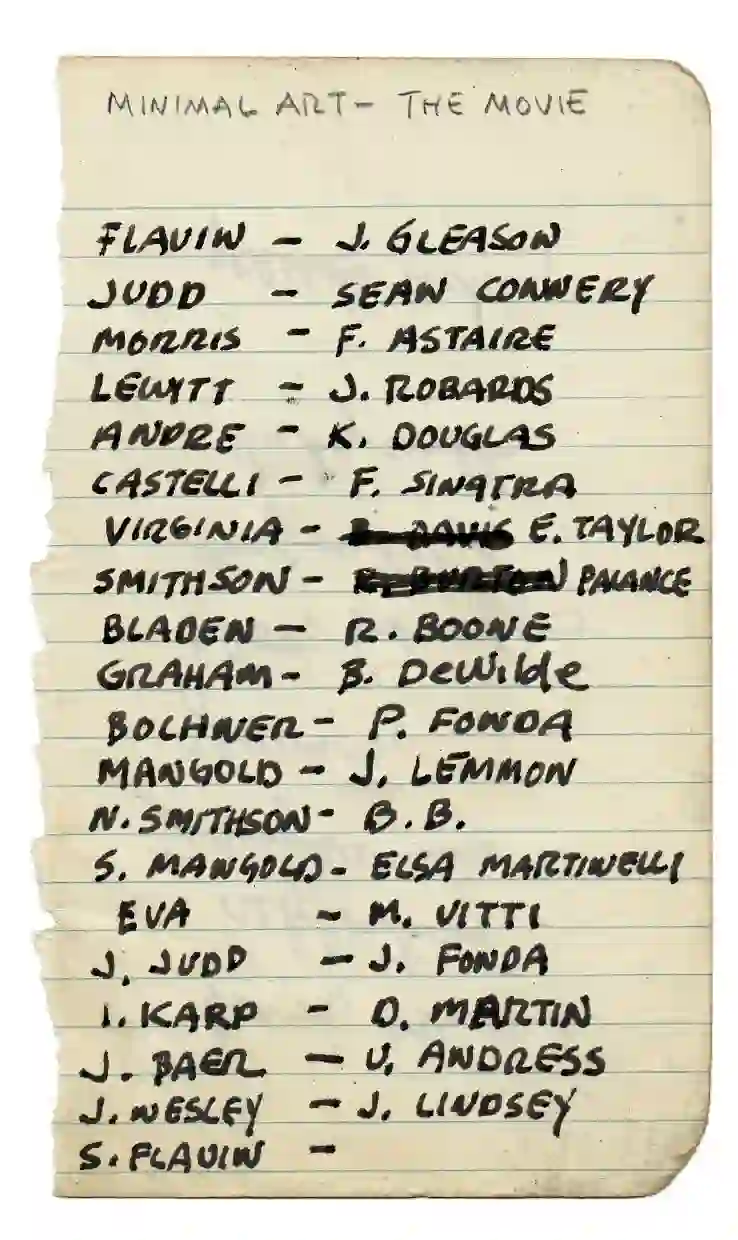

Among the many text-based works in Mel Bochner’s oeuvre is a cast list from 1966 for an imaginary film: Minimal Art—The Movie (fig. 1). The work is written in ink and entitled in graphite (and therefore provisionally, the medium suggests), on a six-by-three-and-a-half-inch piece of notebook paper, ripped out of its binding on the left-hand edge. The list includes two two columns of names: at left, Minimal Art’s protagonists, including artists (Bochner among them), significant others, and dealers associated with the new, predominantly U.S.-American work in three-dimensional art; at right, Bochner’s cast, nearly all Hollywood icons (and Italian American singers, some, members of the Rat Pack), selected to portray Bochner’s friends, fellow artists, and art-world figures. Two names were crossed out and replaced: Virginia [Dwan] would be better played by Elizabeth Taylor than Bette Davis, the strikeout suggests, and Jack Palance would be more suited to play Robert Smithson than Richard Burton. The part of Sonja Flavin (Dan Flavin’s then wife) at the end of the list, remains blank—uncast. Along with the strikethroughs (marks-as-revisions), the blank tells us that the work is a working space. “For me art is a way of thinking about things,” the artist would thereafter say(1).

Minimal Art—The Movie is a “working drawing,” a category of practice Bochner first used in December of that same year in his exhibition of Xeroxed documents, contracts, and plans from him and other artists at the School of Visual Arts Gallery, New York, (Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to be Viewed as Art). A few years later, in a statement for an exhibition of American drawings at Munich’s Galerie Heiner Friedrich in 1969, Bochner defined the category as a “residue of thought, the place where the artist formulates, contrives, and discard his ideas(2).”

I begin with this work in part because of its humor, now recognizable as classic Bochner: It’s a cast for a movie about the famously anti-narrative, anti-representational work of Minimal Art (now known as minimalism). Actors would represent; iconic ones would act dually, by which I mean that we might see cast member Frank Sinatra as both himself and as Leo Castelli, the New York-based gallerist and dealer he’s meant to portray. This text-based, notational work finds a ready formal and conceptual analogue in Bochner’s oeuvre is his contemporaneous text-based “portrait” drawings, including Self/Portrait of 1966. (This work also reflects thinking about self-representation; Bochner casts Peter Fonda as himself, that is, as Mel Bochner). But Minimal Art—The Movie also stands apart. It asks us not to just look at a different kind of picture but to imagine a different one as well—a motion picture—about anti-pictorial art. That alone is enough to make even the most serious of art historians laugh. It’s too good not to note (pun intended).

But as a working drawing, it also cues us to something that has long been overlooked in the formative years of Bochner’s practice: Transatlanticism, specifically between Italy and America. Further evidence from the drawing supports this claim. Two thirds of the way down the list, we find “Eva”—for Eva Hesse, the great artist and Bochner’s dear friend—was to have been played by “M. Vitti”: Monica Vitti, the postwar Italian film star best known as Michelangelo Antonioni’s muse in the early 1960s trilogy on alienation formed by L’Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L’Eclisse (1962), and who had most recently appeared in Red Desert (1964). Indeed, in addition to Vitti as Hesse, Leo Castelli, the Italian dealer or American Pop Art, who earned a U.S. citizenship for intelligence service in World War II, would be played by Frank Sinatra; dealer and Castelli director Ivan Karp would be played by Dean Martin; and Sylvia Mangold (artist Robert Mangold’s wife) would be played by Elsa Martinelli, the Italian film star who had come to fame in the U.S. by appearing in a major picture with Kirk Douglas—also cast in Bochner’s film, as Carl Andre. In retrospect, Minimal Art—The Movie, a seemingly insignificant, inconsequential work in the artist’s practice, gains new valence for the history that Bochner gets to in this exhibition at Magazzino some five decades later. When we look at the work now, it cues us to what Bochner would recount to me as the “odd resonances” between his work and that of artists on the other side of the Atlantic, specifically those in Italy, but also in South America(3). (Fontana, it’s worth noting, was Italian-Argentine, as Iria Candela’s recent exhibition at the Met Breuer has at long last considered more seriously). In this sense, the work is not only a cast. It casts (and through its revisions, recasts). It transmits, it constellates connections, between the New York-centered American art world and Italian culture, both in and outside of New York. The text-based work asks us to imagine the then radical, predominantly American, anti-expressionist, anti-pictorial art of the 1960s as an Italian picture, at least in part. It parries with Bochner’s long exploration of language and pictures; one of his word paintings from 2018, for example, cheekily asks viewers, Do I have to draw you a picture? Other kinds of pictures, like this one, the text-based painting suggests, tell us more. As Wittgenstein had proposed: “Logical pictures can depict the world.”

For historians of Bochner’s work, 1966 was the year that the then twenty-six-year-old wrote a field-shaking review of Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors, curated by Kynaston McShine at the Jewish Museum. In his review in Arts Magazine, Bochner identified the source of subversive attitude of this new work: “it points to the probable end of all Renaissance values(4).” It was also the year that Bochner wrote about Robert Rauschenberg’s series on Dante’s Inferno, exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. In Arts Magazine, Bochner addressed Rauschenberg’s “methodology of reading and illustrating one canto at a time,” citing the artist’s use of personal poetics in place of Dante’s content while lauding his commitment to “the logistics of doing(5).” Bochner would later say that he prefers “doing art” to “making art.”

Minimal Art—The Movie preceded a wave of exhibitions for Bochner in Italy during the formative years of his career. Beginning in 1970, Bochner’s work was exhibited extensively in Italy, where the artist was, in his view, initially better received than in the U.S(6). He was included in Conceptual Art, Arte Povera, Land Art (Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna, Turin, 1970), the international exhibition curated by the late critic, curator, and theorist of Arte Povera, Germano Celant. That same year, he had solo shows at the vanguard Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone in Turin, a space that showcased Arte Povera artists and American Pop in Italy, as well as at the Galleria Toselli in Milan, followed by exhibitions at Bonomo (1972) and Schema Gallery (1974) in Bari and Florence. In 1973, another radical, internationally minded curator of Italian art, Achille Bonito Oliva, included Bochner in the Analitica/Analytic section of the experimental exhibition, Contemporanea, held in the subterranean parking structure of the Villa Borghese in Rome.

I want to suggest that this work and Bochner’s broader engagements with Italy can recast some of our thinking about the global re-imagining of pictorial form that happened in the decades after World War II. In the case of Bochner, Alighiero Boetti (associated with Arte Povera), and Lucio Fontana (associated with Spazialismo): these divergent artists reimagined imagistic pictures and pictorial space (the space of representation) with new terms in real space (“lived space” as Bochner would call it), toward language as (il) logic (or “coherence in incoherence,” as Boetti would explore), and toward an exploration of both space and language as structures of the world(7).

Many of the works in this exhibition ask us to do the same. Bochner’s Language Is Not Transparent (Italian/English) (1970/2019), first executed in English for the Dwan Gallery’s “Language Show” in 1970, asks us to look and to contemplate form and meaning in context, in lived space—specifically in one that seems potentially international in audience. Indeed, in the 1970/2019 execution of Language Is Not Transparent here at Magazzino, Bochner writes the title in both English and Italian on the walls of a U.S.-based institution for postwar Italian art, founded by an American (Nancy Olnick) and an Italian (Giorgio Spanu) in New York. The work asks us to consider the always-already Italian presence in Bochner’s thoughts about language by 1970, and its continued valence for him today.

These points bring new questions to existing discussions about language in Bochner’s work. Yve-Alain Bois has argued that Bochner’s work after 1969 confronted the necessity for taxonomy and the opacity of language. “It is at the very end of the 1960s, I think,” Bois writes, “that Bochner began to realize that his dream of a perfect mapping of the world by language, of a perfect adequacy, was based on the naïve illusion that language was transparent to thought, and that, as a perfectly autonomous, abstract tool it could exhaustively map the world(8).” I wonder if Bochner’s Italian pictures (in text, imagined cinematic form, and geography) and their logic of resonance might be one that gets to the possibilities and complications of translation(9).

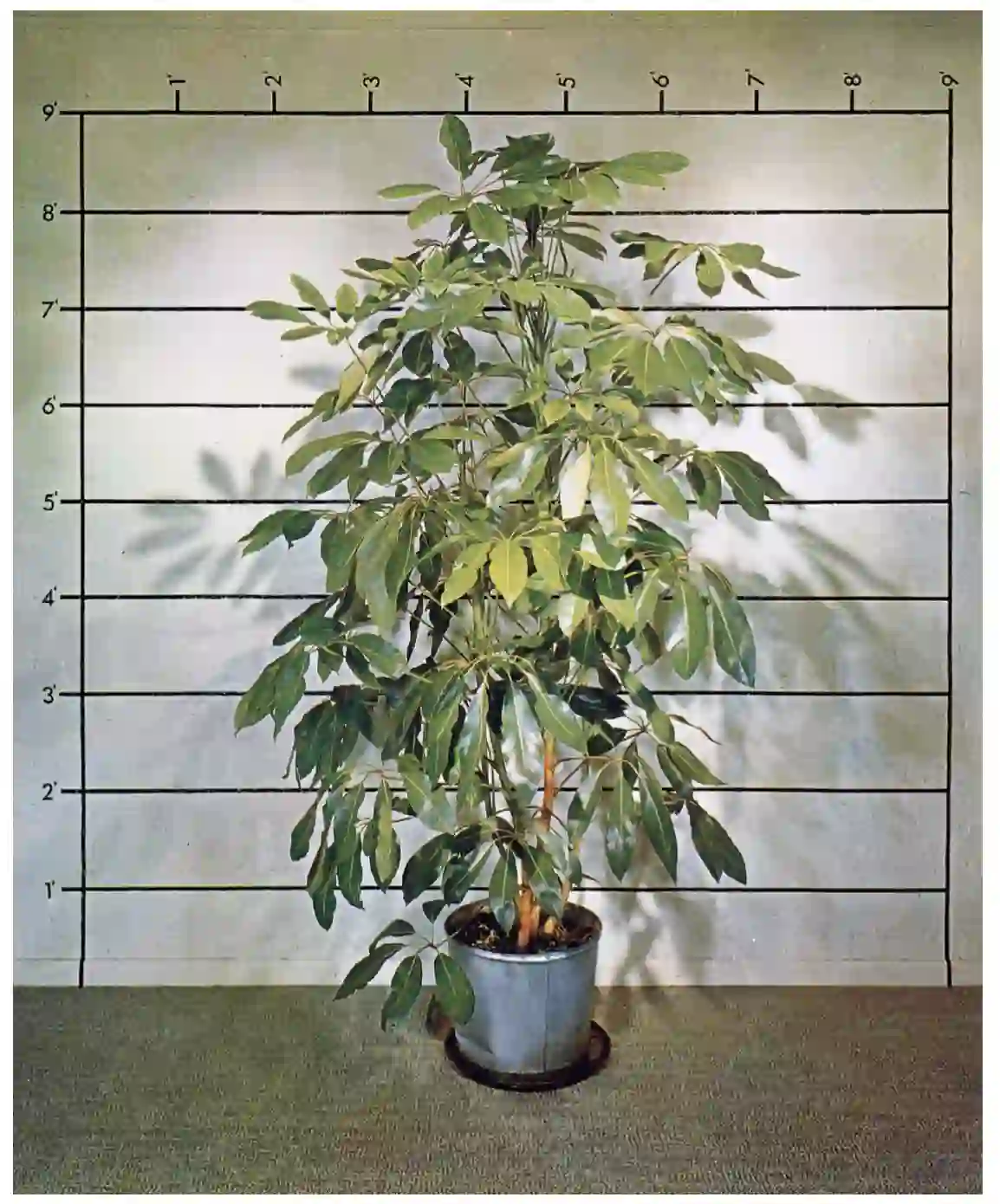

Examination of one of Bochner’s own publications elucidates this point.In February 1972, the second issue of Data (1971–1978), the Italian journal on international contemporary art founded by art critic Tommaso Trini in 1971, published three statements by Bochner, in English and in translated form in Italian, on his Measurements series (fig. 2)(10). His texts were paired with photographs of his works, some of which were noted as having been acquired by vanguard gallerists and artists, both Italian (Sperone and Corrado Levi in Torino) and American. At the beginning of the statements is the now famous photograph of Bochner’s Measurement: Plant (1969), taken at the artist’s 1969 installation at Finch College of Art, New York. The work, the caption states, was owned by Robert Rauschenberg; the picture of the ficus, positioned in front of a measurement wall marked off by tape and Letraset (dry-transfer “instant” lettering), as reprinted in Data with the journal name and issue number in the upper-right-hand corner. Bochner began with an epigraph (in both English and Italian) from Wittgenstein’s notebooks from the mid-1910s: it begins, “I want to report how I found the world.”/“Voglio riferire come io ho scoperto il mondo.” Measuring things was Wittgenstein’s way “to discover the world,” the epigraph tells us. It was Bochner’s way, too. That work—measuring things—was not without work. Rubbing Letraset onto a wall is nothing if not an exercise in patience and precision. The close work between hand and support requires mental concentration and an even, detail-oriented application of physical pressure. The process ultimately recalls the care and intimate work of drawing more than the stick-on- the-wall minimally laborious gesture the end result might appear to index. Measuring things entails an intimate, careful exploration of the world.

Visitors to Bochner Boetti Fontana will find many odd resonances here: the collapse of representation and lived space captured by Fontana’s wall- climbing Quanta (1960) and Bochner’s Measurements series (1968–1971), one legacy of which we see here in Measurement: 12 inches between (1999); the exploration of color and light in Bochner’s recreation in 1993 of one of his pebble floor sculptures from the early 1970s with Fontana’s leftover Murano glass fragments in Meditation on the Theorem of Pythagoras (1972/1993); language as a logic of possibility (and humor) in Fontana’s Io sono un santo (1958); the exploration of geometric systems of order by Bochner and Boetti; the commitment to doing, to process, that we see at the heart of these artists’ respective practices—their ricerca artistica. In so doing, we should also look for these artists’ careful explorations of the world, within the Italian picture that Bochner has brought into view.

For Germano Celant (1940–2020).

Endnotes

Mel Bochner, interview with Elayne Varian (unpublished, March 1969), printed in Solar Systems & Rest Rooms: Writings and Interviews, 1965–2007, xiv (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2008), 57.

Bochner, “Anyone Can Learn to Draw,” in American Drawings (1969), reprinted in Mel Bochner. Drawings 1966–1973 (New York: Lawrence Markey, 1998), 36. Originally published in the brochure for the exhibition held at Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich.

Tenley Bick, interview with Mel Bochner, Magazzino Italian Art (NY Office), January 23, 2020.

M. Bochner, “Primary Structures,” Arts Magazine 40, no. 8 (June 1966): 345 M.B., “In the Museums: Robert Rauschenberg,” Arts Magazine 40, no. 5 (March 1966): 50.

Bick, interview with Bochner, Jan. 23, 2020.

See Bochner, “Walls” (1981), in Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings, edited by Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz, 833 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996). Originally published in Murs (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1981).

Yve-Alain Bois, foreword to Mel Bochner, Solar System & Rest Rooms: Writings and Interviews, 1965–2007, xiv (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2008).

“Resonances” is Bochner’s word, here, but it is also a term that art historian Reiko Tomii has offered to describe transgeographical affinities between disparate practices in art of the global 1960s. I mean it in both senses, here. See Tomii, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016).

See Bochner, “Measurement Series,” Data, no. 2 (February 1972): 62–67.